Sand dollar

| Sand dollars | |

|---|---|

| |

| A live individual of Clypeaster reticulatus (Mayotte) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Echinodermata |

| Class: | Echinoidea |

| Superorder: | Gnathostomata |

| Order: | Clypeasteroida |

| Suborders and families | |

|

See text. | |

Sand dollars (also known as sea cookies or snapper biscuits in New Zealand and Brazil, or pansy shells in South Africa) are species of flat, burrowing sea urchins belonging to the order Clypeasteroida. Some species within the order, not quite as flat, are known as sea biscuits. Sand dollars can also be called "sand cakes" or "cake urchins".[2]

Names

[edit]The term "sand dollar" derives from the appearance of the tests (skeletons) of dead individuals after being washed ashore. The test lacks its velvet-like skin of spines and has often been bleached white by sunlight. To beachcombers of the past, this suggested a large, silver coin, such as the old Spanish dollar, which had a diameter of 38–40 mm.

Other names for the sand dollar include sand cakes, pansy shells, snapper biscuits, cake urchins, and sea cookies.[3] In South Africa, they are known as pansy shells from their suggestion of a five-petaled garden flower. The Caribbean sand dollar or inflated sea biscuit, Clypeaster rosaceus, is thicker in height than most. In Spanish-speaking areas of the Americas, the sand dollar is most often known as galleta de mar (sea cookie); the translated term is often encountered in English.

In the folklore of Georgia in the United States, sand dollars were believed to represent coins lost by mermaids.[4]

Description

[edit]

Sand dollars diverged from the other irregular echinoids, namely the cassiduloids, during the early Jurassic,[5] with the first true sand dollar genus, Togocyamus, arising during the Paleocene. Soon after Togocyamus, more modern-looking groups emerged during the Eocene.[1]

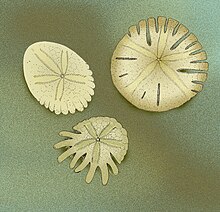

Sand dollars are small in size, averaging from 80 to 100 mm (3 to 4 inches).[6] As with all members of the order Clypeasteroida, they possess a rigid skeleton called a test. The test consists of calcium carbonate plates arranged in a fivefold symmetric pattern.[7] The test of certain species of sand dollar have slits called lunules that can help the animal stay embedded in the sand to stop it from being swept away by an ocean wave.[8] In living individuals, the test is covered by a skin of velvet-textured spines which are covered with very small hairs (cilia). Coordinated movements of the spines enable sand dollars to move across the seabed. The velvety spines of live sand dollars appear in a variety of colors—green, blue, violet, or purple—depending on the species. Individuals which are very recently dead or dying (moribund) are sometimes found on beaches with much of the external morphology still intact. Dead individuals are commonly found with their empty test devoid of all surface material and bleached white by sunlight.

The bodies of adult sand dollars, like those of other echinoids, display radial symmetry. The petal-like pattern in sand dollars consists of five paired rows of pores. The pores are perforations in the endoskeleton through which podia for gas exchange project from the body. The mouth of the sand dollar is located on the bottom of its body at the center of the petal-like pattern. Unlike other urchins, the bodies of sand dollars also display secondary front-to-back bilateral symmetry with no morphological distinguishing features between males and females. The anus of sand dollars is located at the back rather than at the top as in most urchins, with many more bilateral features appearing in some species. These result from the adaptation of sand dollars, in the course of their evolution, from creatures that originally lived their lives on top of the seabed (epibenthos) to creatures that burrow beneath it (endobenthos).

-

Echinocyamus pusillus alive.

-

Living sand dollar.

-

Eccentric sand dollars (Dendraster excentricus) at Monterey Bay Aquarium.

-

Echinarachnius parma (family Echinarachniidae).

-

Clypeaster aegypticus, showing internal buttresses

Suborders and families

[edit]According to World Register of Marine Species:

- sub-order Clypeasterina

- family Clypeasteridae L. Agassiz, 1835

- family Fossulasteridae Philip & Foster, 1971 †

- family Scutellinoididae Irwin, 1995 †

- family Conoclypidae von Zittel, 1879 †

- family Faujasiidae Lambert, 1905 †

- family Oligopygidae Duncan, 1889 †

- family Plesiolampadidae Lambert, 1905 †

- sub-order Scutellina

- infra-order Laganiformes

- family Echinocyamidae Lambert & Thiéry, 1914

- family Fibulariidae Gray, 1855

- family Laganidae Desor, 1858

- infra-order Scutelliformes

- family Echinarachniidae Lambert in Lambert & Thiéry, 1914

- family Eoscutellidae Durham, 1955 †

- family Protoscutellidae Durham, 1955 †

- family Rotulidae Gray, 1855

- super-family Scutellidea Gray, 1825

- family Abertellidae Durham, 1955 †

- family Astriclypeidae Stefanini, 1912

- family Dendrasteridae Lambert, 1900 -- Pacific eccentric sand dollar.

- family Mellitidae Stefanini, 1912 -- Keyhole sand dollars

- family Monophorasteridae Lahille, 1896 †

- family Scutasteridae Durham, 1955 †

- family Scutellidae Gray, 1825

- family Taiwanasteridae Wang, 1984

- family Scutellinidae Pomel, 1888a †

- infra-order Laganiformes

-

Underside of live Mellita quinquiesperforata

-

A number of sand dollars on the seabed

-

Sand dollar beneath the sand at low tide on Hilton Head Island

-

Live sea biscuit, Clypeaster rosaceus, commonly found off Key Biscayne, Florida

Behavior and habitat

[edit]Sand dollars can be found in temperate and tropical zones along all continents.[6] Sand dollars live in waters below the mean low tide line, on or just beneath the surface of sandy and muddy areas. The common sand dollar, Echinarachnius parma, can be found in the Northern Hemisphere from the intertidal zone to the depths of the ocean, while the keyhole sand dollars (three species of the genus Mellita) can be found on many a wide range of coasts in and around the Caribbean Sea.

The spines on the somewhat flattened topside and underside of the animal allow it to burrow or creep through the sediment when looking for shelter or food. Fine, hair-like cilia cover these tiny spines.[9] Sand dollars usually eat algae and organic matter found along the ocean floor, though some species will tip on their side to catch organic matter floating in ocean currents.[8]

Sand dollars frequently gather on the ocean floor, in part to their preference for soft bottom areas, which are convenient for their reproduction.[why?] The sexes are separate and, as with most echinoids, gametes are released into the water column and go through external fertilization. The nektonic larvae metamorphose through several stages before the skeleton or test begins to form, at which point they become benthic.

In 2008, biologists discovered that sand dollar larvae will clone themselves for a few different reasons. When a predator is near, certain species of sand dollar larvae will split themselves in half in a process they use to asexually clone themselves when sensing danger. The cloning process can take up to 24 hours and creates larvae that are 2/3 their original length which can help conceal them from the predator.[10] The larvae of these sand dollars clone themselves when they sense dissolved mucus from a predatory fish. The larvae exposed to this mucus from the predatory fish respond to the threat by cloning themselves. This process doubles their population and halves their size which allows them to better escape detection by the predatory fish but may make them more vulnerable to attacks from smaller predators like crustaceans. Sand dollars will also clone themselves during normal asexual reproduction. Larvae will undergo this process when food is plentiful or temperature conditions are optimal. Cloning may also occur to make use of the tissues that are normally lost during metamorphosis.

The flattened test of the sand dollar allows it to burrow into the sand and remain hidden from sight from potential predators.[8] Predators of the sand dollar are the fish species cod, flounder, sheepshead and haddock. These fish will prey on sand dollars even through their tough exterior.[9]

Sand dollars have spines on their bodies that help them to move around the ocean floor. When a sand dollar dies, it loses the spines and becomes smooth as the exoskeleton is then exposed.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ a b The Paleobiology Database

- ^ Kennedy, Jennifer (9 October 2019). "Sand Dollar Facts". ThoughtCo.

- ^ "Everything You Need to Know About the Sand Dollar". Sand Dollar Shelling. 29 November 2021.

- ^ Bryant, David; Davidson, George (2003). Georgia's Amazing Coast: Natural Wonders from Alligators to Zoeas. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-2533-0.[page needed]

- ^ Kier, Porter M. (January 1982). "Rapid evolution in echinoids". Palaeontology. 25 (1): 1–9. BHL page 49707713.

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of Animals. Great Neck Publishing. 2017.

- ^ "Sand Dollar Printout - Enchanted Learning Software". Enchanted Learning. 2000.

- ^ a b c Grzimek, Bernhard (2004) [2003]. Grzimek's animal life encyclopedia. Neil Schlager, Donna Olendorf, American Zoo and Aquarium Association (2nd ed.). Detroit: Gale. ISBN 0-7876-5362-4. OCLC 49260053.[page needed]

- ^ a b Sayre, April Pulley (1996). Seashore (1st ed.). New York: Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 0-8050-4085-4. OCLC 34516888.[page needed]

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. (May 2008). "Split Defense". Scientific American. 298 (5): 38. Bibcode:2008SciAm.298e..38C. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0508-38b.

- ^ Nelson, Angela (10 June 2022). "9 Fascinating Facts About Sand Dollars". Treehugger.

External links

[edit]- "Clypeasteroida". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- Mooi, Rich (1990). "Paedomorphosis, Aristotle's lantern, and the origin of the sand dollars (Echinodermata: Clypeasteroida)". Paleobiology. 16 (1): 25–48. Bibcode:1990Pbio...16...25M. doi:10.1017/S0094837300009714. JSTOR 2400931.

- Ellers, Olaf; Telford, Malcolm (22 October 1997). "Muscles advance the teeth in sand dollars and other sea urchins". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 264 (1387): 1525–1530. doi:10.1098/rspb.1997.0211. PMC 1688700.

- Stock, Stuart R. (January 2014). "Sea urchins have teeth? A review of their microstructure, biomineralization, development and mechanical properties". Connective Tissue Research. 55 (1): 41–51. doi:10.3109/03008207.2013.867338. PMC 4727832. PMID 24437604.

- The Common Sand Dollar by Cheryl Page

- Video showing the life cycle of Clypeaster subdepressus