August Kekulé

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2015) |

August Kekulé | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Friedrich August Kekulé 7 September 1829 |

| Died | 13 July 1896 (aged 66) |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | University of Giessen |

| Known for | Theory of chemical structure Tetravalence of carbon Structure of benzene |

| Awards | Pour le Mérite (1893) Copley Medal (1885) ForMemRS (1875) |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | University of Heidelberg University of Ghent University of Bonn |

| Thesis | Ueber die Amyloxydschwefelsäure und einige ihrer Salze (1852) |

| Academic advisors | Justus von Liebig |

| Doctoral students | Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff Hermann Emil Fischer Adolf von Baeyer Richard Anschütz |

Friedrich August Kekulé, later Friedrich August Kekule von Stradonitz (/ˈkeɪkəleɪ/ KAY-kə-lay,[1] German: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈʔaʊɡʊst ˈkeːkuleː fɔn ʃtʁaˈdoːnɪts]; 7 September 1829 – 13 July 1896), was a German organic chemist. From the 1850s until his death, Kekulé was one of the most prominent chemists in Europe, especially in the field of theoretical chemistry. He was the principal founder of the theory of chemical structure and in particular the Kekulé structure of benzene.

Name

[edit]Kekulé never used his first given name; he was known throughout his life as August Kekulé. He did however say it once in his work. After he was ennobled by the Kaiser in 1895, he adopted the name August Kekule von Stradonitz, without the French acute accent over the second "e". The French accent had apparently been added to the name by Kekulé's father during the Napoleonic occupation of Hesse by France, to ensure that French-speakers pronounced the third syllable.[2]

Early years

[edit]The son of a civil servant, Kekulé was born in Darmstadt, the capital of the Grand Duchy of Hesse. After graduating from secondary school (the Grand Ducal Gymnasium in Darmstadt), in the fall of 1847 he entered the University of Giessen, with the intention of studying architecture.[3] After hearing the lectures of Justus von Liebig in his first semester, he decided to study chemistry.[3] Following four years of study in Giessen and a brief compulsory military service, he took temporary assistantships in Paris (1851–52), in Chur, Switzerland (1852–53), and in London (1853–55), where he was decisively influenced by Alexander Williamson. His Giessen doctoral degree was awarded in the summer of 1852.

Theory of chemical structure

[edit]In 1856, Kekulé became Privatdozent at the University of Heidelberg. In 1858, he was hired as full professor at the University of Ghent, then in 1867 he was called to Bonn, where he remained for the rest of his career. Basing his ideas on those of predecessors such as Williamson, Charles Gerhardt, Edward Frankland, William Odling, Auguste Laurent, Charles-Adolphe Wurtz and others, Kekulé was the principal formulator of the theory of chemical structure (1857–58). This theory proceeds from the idea of atomic valence, especially the tetravalence of carbon (which Kekulé announced late in 1857)[4] and the ability of carbon atoms to link to each other (announced in a paper published in May 1858),[5] to the determination of the bonding order of all of the atoms in a molecule. Archibald Scott Couper independently arrived at the idea of self-linking of carbon atoms (his paper appeared in June 1858),[6] and provided the first molecular formulas where lines symbolize bonds connecting the atoms. For organic chemists, the theory of structure provided dramatic new clarity of understanding, and a reliable guide to both analytic and especially synthetic work. As a consequence, the field of organic chemistry developed explosively from this point. Among those who were most active in pursuing early structural investigations were, in addition to Kekulé and Couper, Frankland, Wurtz, Alexander Crum Brown, Emil Erlenmeyer, and Alexander Butlerov.[7]

Kekulé's idea of assigning certain atoms to certain positions within the molecule, and schematically connecting them using what he called their "Verwandtschaftseinheiten" ("affinity units", now called "valences" or "bonds"), was based largely on evidence from chemical reactions, rather than on instrumental methods that could peer directly into the molecule, such as X-ray crystallography. Such physical methods of structural determination had not yet been developed, so chemists of Kekulé's day had to rely almost entirely on so-called "wet" chemistry. Some chemists, notably Hermann Kolbe, heavily criticized the use of structural formulas that were offered, as he thought, without proof. However, most chemists followed Kekulé's lead in pursuing and developing what some have called "classical" structure theory, which was modified after the discovery of electrons (1897) and the development of quantum mechanics (in the 1920s).

The idea that the number of valences of a given element was invariant was a key component of Kekulé's version of structural chemistry.[8] This generalization suffered from many exceptions, and was subsequently replaced by the suggestion that valences were fixed at certain oxidation states.[9] For example, periodic acid according to Kekuléan structure theory could be represented by the chain structure I-O-O-O-O-H. By contrast, the modern structure of (meta) periodic acid has all four oxygen atoms surrounding the iodine in a tetrahedral geometry.[10]

Benzene

[edit]

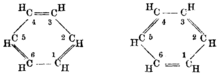

Kekulé's most famous work was on the structure of benzene.[3] In 1865 Kekulé published a paper in French (for he was then still in Belgium) suggesting that the structure contained a six-membered ring of carbon atoms with alternating single and double bonds.[11] The following year he published a much longer paper in German on the same subject.[12]

The empirical formula for benzene had been long known, but its highly unsaturated structure was a challenge to determine. Archibald Scott Couper in 1858 and Joseph Loschmidt in 1861 suggested possible structures that contained multiple double bonds or multiple rings, but the study of aromatic compounds was in its earliest years, and too little evidence was then available to help chemists decide on any particular structure.

More evidence was available by 1865, especially regarding the relationships of aromatic isomers. Kekulé argued for his proposed structure by considering the number of isomers observed for derivatives of benzene. For every monoderivative of benzene (C6H5X, where X = Cl, OH, CH3, NH2, etc.) only one isomer was ever found, implying that all six carbons are equivalent, so that substitution on any carbon gives only a single possible product. For diderivatives such as the toluidines, C6H4(NH2)(CH3), three isomers were observed, for which Kekulé proposed structures with the two substituted carbon atoms separated by one, two and three carbon-carbon bonds, later named ortho, meta, and para isomers respectively.[13]

The counting of possible isomers for diderivatives was, however, criticized by Albert Ladenburg, a former student of Kekulé, who argued that Kekulé's 1865 structure implied two distinct "ortho" structures, depending on whether the substituted carbons are separated by a single or a double bond.[14] Since ortho derivatives of benzene were never actually found in more than one isomeric form, Kekulé modified his proposal in 1872 and suggested that the benzene molecule oscillates between two equivalent structures, in such a way that the single and double bonds continually interchange positions.[15][16] This implies that all six carbon-carbon bonds are equivalent, as each is single half the time and double half the time. A firmer theoretical basis for a similar idea was later proposed in 1928 by Linus Pauling, who replaced Kekulé's oscillation by the concept of resonance between quantum-mechanical structures.[17]

Kekulé's dream

[edit]

The new understanding of benzene, and hence of all aromatic compounds, proved to be so important for both pure and applied chemistry after 1865 that in 1890 the German Chemical Society organized an elaborate appreciation in Kekulé's honor, celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of his first benzene paper. Here Kekulé spoke of the creation of the theory. He said that he had discovered the ring shape of the benzene molecule after having a reverie or day-dream of a snake seizing its own tail (this is an ancient symbol known as the ouroboros).[18]

Another depiction of benzene had appeared in 1886 in the Berichte der Durstigen Chemischen Gesellschaft (Journal of the Thirsty Chemical Society), a parody of the Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft, only the parody had six monkeys seizing each other in a circle, rather than a single snake as in Kekulé's anecdote.[19] Some historians have suggested that the parody was a lampoon of the snake anecdote, possibly already well-known through oral transmission even if it had not yet appeared in print.[20] Others have speculated that Kekulé's story in 1890 was a re-parody of the monkey spoof, and was a mere invention rather than a recollection of an event in his life.

Kekulé's 1890 speech,[21] in which these anecdotes appeared, has been translated into English.[22] If one takes the anecdote as reflecting an accurate memory of a real event, circumstances mentioned in the story suggest that it must have happened early in 1862.[23]

He told another autobiographical anecdote in the same 1890 speech, of an earlier vision of dancing atoms and molecules that led to his theory of structure, published in May 1858. This happened, he claimed, while he was riding on the upper deck of a horse-drawn omnibus in London. Once again, if one takes the anecdote as reflecting an accurate memory of a real event, circumstances related in the anecdote suggest that it must have occurred in the late summer of 1855.[24]

Works

[edit]- Lehrbuch der Organischen Chemie (in German). Vol. 1. Erlangen: Enke. 1859–1861.

- Lehrbuch der Organischen Chemie (in German). Vol. 2. Erlangen: Enke. 1862–1866.

- Lehrbuch der Organischen Chemie (in German). Vol. 3. Erlangen: Enke. 1867.

- Lehrbuch der Organischen Chemie (in German). Vol. 4. Stuttgart: Enke. 1880.

- Lehrbuch der Organischen Chemie (in German). Vol. 5. Stuttgart: Enke. 1881.

- Lehrbuch der Organischen Chemie (in German). Vol. 6. Stuttgart: Enke. 1882.

- Lehrbuch der Organischen Chemie (in German). Vol. 7. Stuttgart: Enke. 1887.

Honors

[edit]

In 1895, Kekulé was ennobled by Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, giving him the right to add "von Stradonitz" to his name, referring to a possession of his patrilineal ancestors in Stradonice, Bohemia. His name thus became Friedrich August Kekule von Stradonitz, without the French accent on the last "e" of his name, and this is the form of the name that some libraries use. This title was inherited by his son, genealogist Stephan Kekule von Stradonitz. Of the first five Nobel Prizes in Chemistry, Kekulé's former students won three: van 't Hoff in 1901, Fischer in 1902 and Baeyer in 1905.

A larger-than-life monument of Kekulé, unveiled in 1903, is situated in front of the former Chemical Institute (completed 1868) at the University of Bonn. His statue is often humorously decorated by students, e.g. for Valentine's Day or Halloween.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Kekulé's formula". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Nickon, Alex; Silversmith, Ernest F. (22 October 2013). Organic Chemistry: The Name Game: Modern Coined Terms and Their Origins. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4831-4523-5.

- ^ a b c Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 717–718.

- ^ Aug. Kekulé (1857). "Über die s. g. gepaarten Verbindungen und die Theorie der mehratomigen Radicale". Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 104 (2): 129–150. doi:10.1002/jlac.18571040202.

- ^ Aug. Kekulé (1858). "Ueber die Constitution und die Metamorphosen der chemischen Verbindungen und über die chemische Natur des Kohlenstoffs". Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 106 (2): 129–159. doi:10.1002/jlac.18581060202.

- ^ A.S. Couper (1858). "Sur une nouvelle théorie chimique". Annales de chimie et de physique. 53: 488–489.

- ^ Alan J. Rocke (2010). Image and Reality: Kekulé, Kopp, and the Scientific Imagination. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-72332-7.

- ^ "Historical Data Concerning the Discovery of the Law of Valence". American Journal of Mathematics. 1 (3): 282. 1878. doi:10.2307/2369316. ISSN 0002-9327. JSTOR 2369316.

- ^ Constable, Edwin C. (22 August 2019). "What's in a Name?—A Short History of Coordination Chemistry from Then to Now". Chemistry. 1 (1): 126–163. doi:10.3390/chemistry1010010. ISSN 2624-8549.

- ^ PubChem. "Periodic acid". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- ^ Aug. Kekulé (1865). "Sur la constitution des substances aromatiques". Bulletin de la Société Chimique de Paris. 3 (2): 98–110.

- ^ Aug. Kekulé (1866). "Untersuchungen uber aromatische Verbindungen". Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 137 (2): 129–196. doi:10.1002/jlac.18661370202.

- ^ "Friedrich August Kekule von Stradonitz –inventor of benzene structure – World Of Chemicals". worldofchemicals.com. 28 May 2015. Archived from the original on 10 November 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ Ladenburg, Albert (1869) "Bemerkungen zur aromatischen Theorie" (Observations on the aromatic theory), Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft, 2 : 140–142.

- ^ Kekulé, August (1872). "Ueber einige Condensationsproducte des Aldehyds (On some condensation products of aldehydes)". Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie (in German). 162 (2–3). Wiley: 309–320. doi:10.1002/jlac.18721620211. ISSN 0075-4617.

- ^ Pierre Laszlo (April 2004). "Book Review: Jerome A. Berson: Chemical Discovery and the Logicians' Program. A Problematic Pairing, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2003". International Journal for Philosophy of Chemistry. 10 (1). Hyle. ISSN 1433-5158. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ Pauling, Linus (1 April 1928). "The Shared-Electron Chemical Bond" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 14 (4): 359–362. Bibcode:1928PNAS...14..359P. doi:10.1073/pnas.14.4.359. PMC 1085493. PMID 16587350. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ Read, John (1957). From Alchemy to Chemistry. Courier Corporation. pp. 179–180. ISBN 978-0-486-28690-7.

- ^ Translated into English by D. Wilcox and F. Greenbaum, Journal of Chemical Education, 42 (1965), 266–67.

- ^ A.J. Rocke (1985). "Hypothesis and Experiment in Kekulé's Benzene Theory". Annals of Science. 42 (4): 355–81. doi:10.1080/00033798500200411.

- ^ Aug. Kekulé (1890). "Benzolfest: Rede". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 23 (1): 1302–11. doi:10.1002/cber.189002301204.

- ^ O. T. Benfey (1958). "August Kekulé and the Birth of the Structural Theory of Organic Chemistry in 1858". Journal of Chemical Education. 35 (1): 21–23. Bibcode:1958JChEd..35...21B. doi:10.1021/ed035p21.

- ^ Jean Gillis (1966). "Auguste Kekulé et son oeuvre, realisee a Gand de 1858 a 1867". Mémoires de l'Académie Royale de Belgique. 37 (1): 1–40.

- ^ Alan J. Rocke (2010). Image and Reality: Kekulé, Kopp, and the Scientific Imagination. University of Chicago Press. pp. 60–66. ISBN 978-0-226-72332-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Benfey, O. Theodor. "August Kekule and the Birth of the Structural Theory of Organic Chemistry in 1858." Journal of Chemical Education. Volume 35, No. 1, January 1958. p. 21–23. – Includes an English translation of Kekule's 1890 speech in which he spoke about his development of structure theory and benzene theory.

- Rocke, A. J., Image and Reality: Kekule, Kopp, and the Scientific Imagination (University of Chicago Press, 2010).

External links

[edit]- Kekulés Traum (Kekulé's dream, in German)

- Kekulé: A Scientist and a Dreamer

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- 1829 births

- 1896 deaths

- 19th-century German chemists

- Scientists from Darmstadt

- People from the Grand Duchy of Hesse

- German organic chemists

- German untitled nobility

- University of Giessen alumni

- Academic staff of the University of Bonn

- Recipients of the Copley Medal

- Foreign members of the Royal Society

- Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences

- Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class)